Transforming and expanding a factory into a series of interconnected buildings.

Sobinco Campus

Location: Zulte, Belgium

Year: 2018–ongoing

Client: Sobinco

Type: Industrial, office

Size: 22,500 m2

Status: Tender Design/estimated completion 2022.

Architects: CCXD + DROM

Collaborators: Bureau Bouwtechniek, MEP Consultants - Estema, Structural Engineers - Mouton

Under construction

Under construction

Introduction

Introduction

Sobinco is a company in Belgium that is specialized in the production of a complete range of fittings for aluminum windows and doors. There are currently about 350 employees working and more than 90% of Sobinco’s products are manufactured by the company itself. All production processes, from raw materials to finished products, are carried out within the grounds of the company.

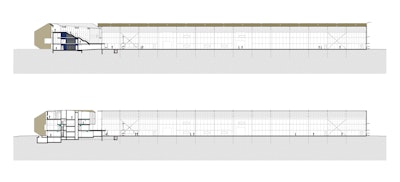

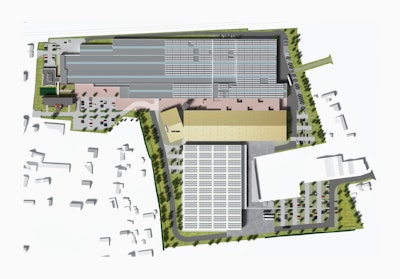

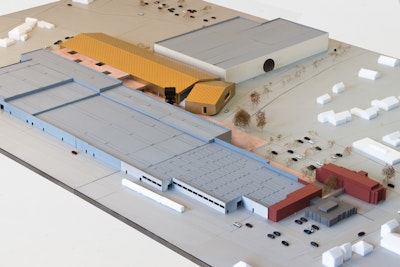

The existing 30,000m2 factory building configuration and layout is a result of an additive and gradual process of construction that was conducted over a period of almost sixty years of the business’s operations and development. The newly planned expansion is unprecedented in its history. The factory will almost double its floor area by 2022. For the past two years, CCXD and DROM have worked together on the development of a masterplan, a new production hall, warehouse, offices and showroom.

A short history of industrial architecture

A short history of industrial architecture

The history of industrial architecture in the 20th Century can be divided into three periods with three distinct approaches.

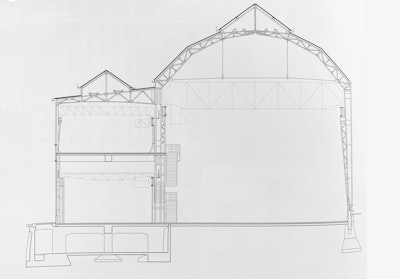

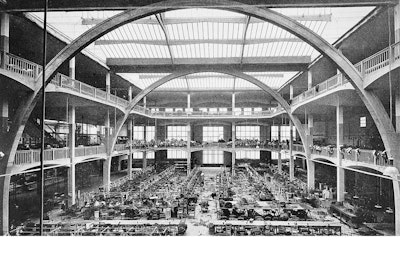

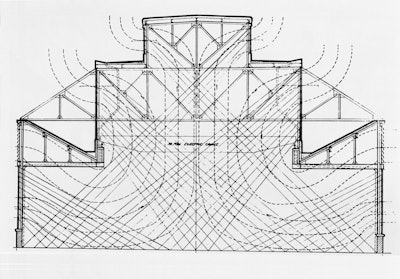

From the late 19th century until the 1960, industrial architecture combined utilitarianism and multiple expressive Geometrical Manoeuvres. These performance-driven factory designs were defined by natural lighting and ventilation, generating a series of fantastic buildings by for example: Robert Maillart, August Perret, Pier Luigi Nervi, Felix Candela and Albert Kahn. They responded to the question of comfort and performance through simple architectural solutions which were inseparable from their building systems. In fact, these systems were taken as potential to rethink and define the architecture, all the while underscoring the ecological consciousness.

From the 1960’s onwards, we enter a “dark zone” where post-war technologies such as air-conditioning and artificial lighting made the need for good architecture obsolete. These lifeless “big boxes” are cheap and easy to build. Until the 1990’s a multitude of high-tech systems were added to the sealed boxes supposedly to improve the efficiency of production. Windows for daylight, natural ventilation and heat exhaustion were considered unimportant.

From the 1990’s onwards, factories were gradually rediscovered as a neglected building type and by today we can see that multiple businesses invest in new factories that are not only efficient in production, but also create a performative architecture. Performance refers to buildings that are more proactive in conditioning and changing the environments they effect. They no longer merely offer functions passively, but fundamentally change an architectural condition dynamically. This of course has a positive effect on the work environment for both white and blue collar workers.

(Reference image from the book: Space of Production, Edited by Jeanette Kuo)

The industrial typology — liberated from a dogmatic program

The industrial typology — liberated from a dogmatic program

Designed for ultimate flexibility , the space of production is programmatically indeterminate. Flexibility is the context, however does not imply the abandonment of rationality, but in fact the opposite. To enable a dynamic environment, the elements that will necessarily remain static need to be defined. Comfort, atmosphere, light and structure are universal criteria that extend—beyond the loose fit of program and form—towards an expression of performance. This pragmatism inherent in the typology leads to the search for creative solutions within a given set of constraints. These constraints and contradictions have prompted creative manipulations of architectural elements, confronting our discipline at its most raw and fundamental.

For most typologies—museums, schools, airports, libraries—architecture relies on program-driven propositions, so much so that cleverly reorganised program would often obscure all other aspects of the architecture that is left unaddressed. Constructive elements, structure and most of all beautiful architectural space has to take a back seat. In the industrial typology we can ones again focus on the architectural language of systems, tectonics and structure. The column, the beam, the arch, the vault and a myriad of other possible types become the primary cast in the search for material ecology.

(Reference: Space of Production, Edited by Jeanette Kuo)

Masterplan

Masterplan

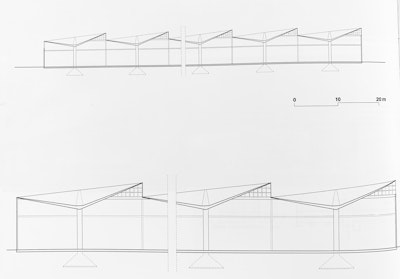

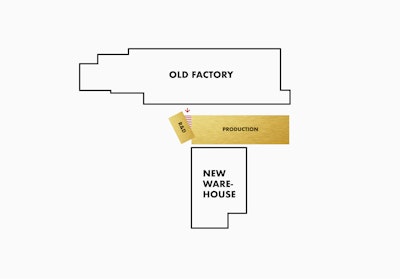

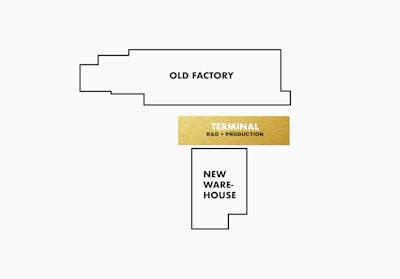

We are addressing this scale of growth in a new way for the company. We propose a masterplan in which we separate the new development into parts, creating a repertoire of distinct buildings with characteristic architecture, while targeting the allocation of the investment. The site will transform from a factory into a new Industrial Campus. It will be the face of the company as it continues to grow on the international market.

Design: Make the invisible visible

Design: Make the invisible visible

It is the ambition to create an architecture that represents the company’s values and makes the Sobinco brand visible to the architectural community through its own architectural presence. It is also crucial to create a vital and engaging working environment to be competitive and attract talent. But also to create spaces where people communicate, interact, and are, well, happy and motivated.

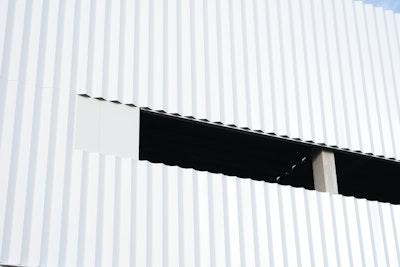

The company produces mechanisms for thresholds (doors, windows) of contemporary buildings, but these mechanisms remain mostly invisible for the general consumer. We based our design on a strategy to reveal the hidden processes of the production cycle and to articulate spatially and aesthetically the thresholds between the interconnected buildings of the campus. This also generates a level of transparency—a visual transition.

Jean Baudrillard: “ Transparency is something extraordinary that expresses the play of light, with something that appears and disappears, but at the same time you get the impression that it involves a subtle form of censorship.

Buildings

Buildings

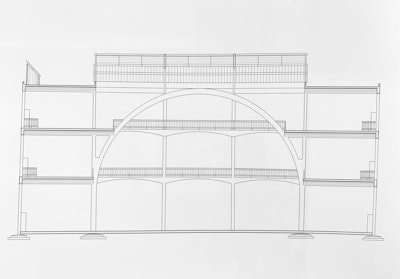

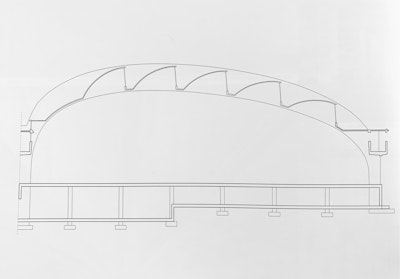

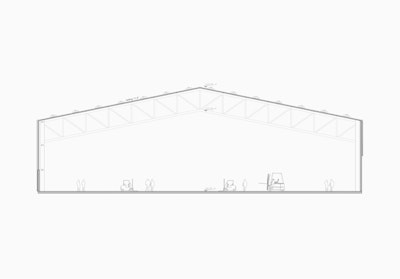

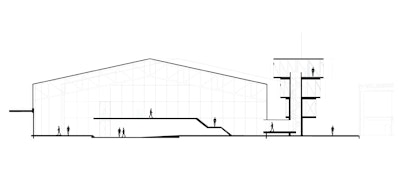

The Golden Terminal will be the primairy new production hall and is 157m long and spans 47m. This building is sliced and hinges open into two parts. The smaller half will be dedicated to the main R&D offices and the larger half will be a column-free production hall for assembling and testing the company’s products. They are two parts of a whole, the offices and production are at the same time visually and physically disconnected and intertwined. In the fracture between those two buildings, a monumental and dramatic main entrance appears.

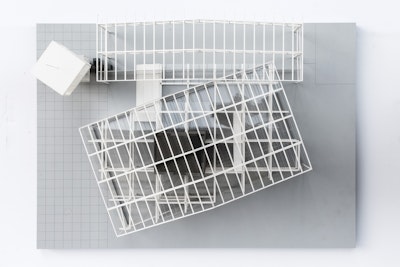

The Sobinco Tower is the creative heart of the company. This architectural folie— based on the concept of a radio tower gathering and distributing information—is where ideas are born and where information is transformed into innovative products. The tower, a stack of three steel frame boxes, provides a place to work undisturbed with a 360° view. It is pure structure, it is architecture naked, in full exposure.

The Connector offices are squeezed in between the old factory and the new Golden terminal. These offices connect the old and the new. From these offices the team managers have a visual overview of the entire production process and are in close proximity to the factory grounds.

Through this design for the Sobinco Factory, It is our aim to bring back what made those early 20th century types compelling: natural light, structural inventiveness, serialism, adaptability and flexibility over time, and the aspect of the workplace. Equally important is to adapt the factory as a whole to the ecological and energy requirements of today and prepare it for the future. At a time when we are increasingly conscious of our resources and of the associated social and ecological responsibilities, the life of a building and its durability, in physical and cultural terms becomes highly relevant.

Gallery